Remembering Gaymon Bennett

On February 1, 2024, our community suffered the loss of a compassionate leader and visionary intellectual. Dr. Gaymon Bennett, Director of the Lincoln Center of Applied Ethics, passed away after a three-year long battle with lung cancer. Gaymon modeled compassion, joy, and an ethic of care in every facet of his work. He emphasized the importance of "being real" and "raising all voices" (see our Guidelines for Good Play), and he deeply understood the transformative power that storytelling has on the spirit and soul. In his scholarship, and during his years serving as our Associate Director (2020-2023) and then Director, he sought to explore how we might imagine new ways to flourish together, in community.

In the spirit of "being real," we asked our longtime collaborators and friends to share stories of their time spent with Gaymon. These reflections on the fundamental imprint that Dr. Gaymon Bennett impressed on us here at ASU and beyond are shepherded by the words of our former Director, Dr. Elizabeth Langland. Stories follow, and these remembrances are held at the close by Tamara Christensen, our close collaborator, friend, and Gaymon's partner in life.

If in reading this collection, you feel called to send us a memory or story, please contact us at [email protected].

In Memoriam: Gaymon Bennett

by Elizabeth Langland

Gaymon Bennett was an extraordinary man. Meeting him, I was immediately impressed by his passion for his work and his perception of how to advance that work and its importance.

The occasion of our meeting was my post-retirement return to Arizona State University in 2016 as a consultant, invited by Deans Kenney and Justice to assess the success to date and ongoing viability of the School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies (SHPRS). The consultancy involved numerous meetings over several days with faculty, students, and staff. Gaymon had just arrived at ASU as an assistant professor in SHPRS, and among his cohort he was eloquent regarding the potential of ASU and SHPRS. He recognized the interdisciplinary school as a model capable of yielding truly innovative and ground-breaking research from its faculty, and his eloquence on the subject persuaded me of the rightness of his vision. And frankly, I loved his irreverent claim that at ASU he would be able to “innovate the s*** out of everything.

No doubt it was young and inspiring faculty like Gaymon who partially influenced my decision to return to ASU in 2017 for a one-year stint as Interim Dean of Humanities in CLAS. I once again encountered Gaymon, now representing SHPRS at a Directors’ meeting when the Director was out of town. The meeting’s topic was important: what should I share with the newly hired, incoming dean about the humanities, its goals, and aspirations. In a few trenchant sentences, Gaymon persuaded me that the future of the humanities would be deeply bound up with emerging technologies, and that it was important to stay attuned to its rapid development and sweeping social and personal impacts.

As a result of his perceptive comments, I invited him to meet with me—a meeting that he claimed to fear was the equivalent of a refractory student being summoned to the principal’s office. But that meeting, in fact, set the direction and course of our collaboration for the next five years, first in the Humanities Institute, where we, with Liz Grumbach, sponsored the first humanities symposium to be held at ASU’s Barrett and O’Connor Washington Center. Entitled “The Future of Humane Technologies,” the symposium brought together distinguished scholars to explore the need to recenter the human in our study and understanding of the technoscape.

In short, rather than assume humans should simply adapt to emerging technologies, which were outpacing our capacity to foresee what were often disastrous consequences, Gaymon insisted that we prioritize human needs and desires and assess emerging technologies in light of their capacity to enhance human life.

But Gaymon was not naïve about the difficulty of prioritizing the “human” in a landscape crowded with emerging technologies that even the most ardent Silicon Valley advocates had to admit had lost their guardrails. The work of re-centering the human became the focus of our collaboration in the Lincoln Center for Applied Ethics, where Gaymon led the development and creation of participatory, action-oriented design studios, which have provided not only an important mode of inquiry for critiquing emerging technologies but also a thoughtful process for re-centering human needs and values in a rapidly evolving world.

Our time with Gaymon has been too short; he had yet so much to contribute. But we are, and will remain, profoundly grateful for the many contributions that Gaymon has made to our institutional, intellectual, and individual lives. Those will live on.

Sarah Florini, Interim Director

Gaymon’s unique impact is evident in the many brilliant and empathetic people he drew to him and who mourn his loss. The Lincoln Center – its amazing team, the work they do, and the deep care with which they do it – are all a testament to his spirit of sincerity, curiosity, and kindness. It is a legacy we cherish and will carry with us always.

Taylor Genovese

I first met Gaymon in his office on March 2, 2017 while visiting ASU for a prospective student visit. I remember we immediately sparked a connection while sharing our personal and academic interests and he ended our short conversation with something along the lines of, “your choice seems like a no-brainer, we need to work together.” After I left his office, I called my partner and we both agreed that this kind of instantaneous connection was kismet and shouldn’t be ignored.

That Fall, Gaymon and I started our work together and we didn’t stop until his passing. We organized reading groups on science, technology, and religion; we began to collaborate with scholars, artists, and professionals to discuss the serious play of humane technology, soulwork, and enchantment, mostly through Design Studios facilitated by the Lincoln Center; we assembled academic panels and roundtables; we collaborated on multimodal projects; and finally, he integrated me into the Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict’s Beyond Secularization project, where he supervised the majority of my dissertation. Twice a week, starting in 2020, we also began co-writing what we hoped would be a monograph on the moral realities of good and evil. Part of my mourning Gaymon has been mourning our future work together. I had hoped and planned for a lifelong collaborative relationship with him.

But our connection was one that went beyond the often-strict teacher-student duality. We also quickly became friends. We would talk about good rock climbing and hiking spots, share and commiserate about the ups and downs in each other’s lives, eat meals and mix cocktails together, spend long nights talking around his backyard fire pit, and share particularly interesting or insightful tarot draws. After his diagnosis, I connected him with my mother, who has survived four rounds of cancer, including lung cancer. I know their relationship formed quickly and strongly and they were each a comfort in each other’s lives.

As Gaymon’s last student (he was brought to the hospital mere hours after my dissertation defense), I also mourn the fact that his brilliant and caring mentorship will no longer be experienced by future students.

I was incredibly lucky to have known Gaymon Bennett—to have been guided by him, cared for by him, challenged by him. I am going to miss him immensely for the rest of my life. Yet, while it is healthy to mourn the man, it is also important to remember that a life is not over when a body dies. Gaymon lives on in the way that I look at the world, the way that I think, the way that I teach my students, the way that I approach mentorship, and the way that I love my friends and family. And I know I am not alone. Anyone who experienced Gaymon’s unique blend of intensity and clarity in the way he communicated his intellectual and affective ideas will also carry a piece of his light in the world. And for that, we can all be comforted and grateful. It was his last gift to us. Selah.

Katina Michael

This man was transformative.

He managed to unlock, and unblock, something that was buried deep within my soul.

He taught me about the word “soulful”. Elizabeth Langland was on that call, in preparation for one of the first design studios. It was 2 am Australia time. He was so patient. And listened and felt every word though I was so exhausted.

He gave me the guts and confidence to do something I would never have otherwise done. He was a builder in self-belief; somehow so assured and assuring all of us. Our journey is not “by ourselves”, but together. Feel safe. Even when you doubt. Feel ok because tomorrow will come. That was what I felt of him.

And those eyes; piercing. My husband has the same eyes, so I can say that. And people often comment about my husband’s eyes. It was not the shape nor the color of Gaymon’s, because I never saw them in real life. Only once I noticed Gaymon sitting at the ASU courtyard from the side of my view, where I was having a curriculum meeting with the Critical Data Scientists from West campus, and by the time I finished my meeting, he was gone. And we never said “hello” in person… but those eyes, even via Zoom which is so bland a medium… they had depth and mystery and the wonderment of Life.

I feel so fortunate that our lives crossed, and that he somehow brought us all together. How’s that. Our design studios have sustained me for 4 years. And when someone said 4 years the other day, I could not believe it was 4 years… because being with you all, seems like never enough time.

I will tell you something I also viscerally feel, and I wonder what some of you will make of it. In the early days of our design studios, there was a certain precision I can’t really figure out. And when I listened to each of you, it was like every word was crisp, and the silence itself was speaking, in between screens. I don’t know how you recreate that, and I don’t know what that was. Ok, some might say preparation… but not so, it was a spiritual kind of quiet… one where you could imagine heaven was here on earth for that split second. People were speaking, but there was no sound… I can’t explain it… All of you, thank you for bringing that to a digital medium when that can only be experienced on analogue (and rarely)! Somehow you’ve done the impossible.

Sending love and celebration for a life well lived. He’s with us, smiling, and encouraging us onward.

Adam (Max) Gabriele

I think what is preserved is more important, like the soul of the person and the essence of memory rather than its furniture. It is the same now with Gaymon. To some extent, as is often the case in the immediate shadow cast by a death, much of what I can recall is frustrating - the desire to have been closer with him, to have had more of his time, to have had answers to particular questions. I have only snippets right now - his deep and infectious laugh, the image of him spreading his arms like a beatboxer while skateboarding and listening to Kendrick Lamar, saying Kendrick Lamar was a genius with the same admiration as he had for Max Weber, or Foucault, or Certeau. I always respected that he was so honest - about the trauma so often inherent in academic politics and the callousness of some of his own mentors, about his own inconsistencies and emotions. Most of all I remember his compassion and drive toward empathy. To see his eyes well with tears at the stories of inner city youths in San Francisco or at a moving passage in something he was reading... it was so gorgeously human. I have an image of him, eyes sparkling with tears, but laughing also at an inherent irony. That facility of spirit, to move so freely between emotions, will ensure that he has moved, is moving with equal grace into whatever mode of being awaits us all. I always appreciated how he gave credit to his students and colleagues when one of their ideas led to a more generative avenue of thought for him. I knew from the moment I met him that, of all the people I had met since returning to school, that I wanted not to be him but to be a man inflected by him. I received the news of his passing on my 40th birthday, and all I could think was how much I wished we had been able to be old men together. I loved him very much and while I cannot grasp a particular story to bring to the surface right now, the pool in which those memories rest is profoundly deep. I will miss him, and what more appropriate thing can we say about those we have loved and lost?

Purdom Lindblad

My heart is grieving and sharing the joy and love of Gaymon. I’m grateful for his generosity and skill in gathering us together, pulling the best ideas from each of us.

Often I think about Gaymon’s invitation for communication rooted in intimacy and for attending to that which is precious. Things not often found in my work life, so doubly precious in our cohort. I am thankful to know and share time with each of you; thankful for your fingerprints on my heart and mind.

Erica O'Neil

I am heartened by the memories of the tremendous impact a soul like Gaymon’s has had on the world. He helped to shape me as a scholar, colleague, collaborator, and friend, and our conversations were always meandering, expansive, and generative. I’ll admit to hoarding memories like a possessive dragon, and even now the wound is too fresh to offer those jewels freely. But as I look at my own workspace, I can see Gaymon’s impact on my life, reflected back as colorful jewels. He adored the sticky note as brainstorming, note taking, and visualizing tool. Our brainstorming sessions always looked like a technicolor version of a noir detective’s evidence gathering board, and I admit that this is one of the many impacts he has had on my life—the sticky note method has absolutely infected my life both personally and professionally!

But for now, I’ll focus primarily on our professional work together and the many projects we brought into the world. The one which was the most impactful to me personally has to be the Craftwork as Soulwork project, which bookended our time together, as the first and last research focus we worked on. It also has the distinction of imparting skills and practices that informed Gaymon’s own end-of-life journey, and has helped with my own healing process.

We met at a Lincoln Center for Applied Ethics research symposium shortly after Gaymon’s arrival at ASU, and by 2018 we began to apply for grants to fund research into how to cultivate cultures of ethical STEM through personal moral formation. Our idea revolved around translating historical models and techniques of apprenticeship, character building, and initiation—namely spiritual models of character formation—in ways that allowed for the personal and professional growth of scientists.

Anyone who spent time with Gaymon knows that he lived the phrase, “The work you do works you.” And we wanted to find a way to test that more broadly across laboratories at ASU.

While the initial grant application went unfunded, we moved through several revisions of the “Sanctifying Science” project until we arrived at “Craftwork as Soulwork,” a description that centered “the work” as instrumental to the type of person we become by doing it. Our project secured a funder in 2021, the John Templeton Foundation, and we embarked on a set of experiments with both experts in spiritual formation and scientists from across ASU. Over the course of two years, we hosted off-campus retreats at Spirit in the Desert, and engaged with experts in: writing as soulwork, meditation as soulwork, compassion and gratitude as soulwork, chant as soulwork, presence as soulwork, and pilgrimage as soulwork. I am forever grateful that I got to spend so much time with Gaymon through planning and practicing these spirit-sustaining techniques, and that Gaymon introduced me to Gil Stafford along the way, his long-term friend, spiritual advisor, and primary soulwork expert on the project.

As Gaymon’s journey with cancer progressed from curative to palliative, Gil and I continued to work on the Craftwork as Soulwork project to bring a final version of the toolkit into the world. (You can access the work here “The Integrity Toolkit: Techniques and Tools for Conscientious Productivity.” Clicking the link launches the toolkit and prompts you to make a copy, which will allow you to edit the slides as your personal reflection deck as you work through the exercises.) At the same time as we were finishing the toolkit, Gaymon was also exercising the practices of presence and other tools we investigated on the project. He also continued to “do the work,” by contributing to his book on the soul, and in the process that helped him to come to terms with how to “transmute out of being alive.”

I’ll let him explain it in his own words from a January 2024 conversation:

|

“The question of the work is a question itself. As much as I long to know what the work is—like an athlete or a musician, who can just get down to work they know—I think there's still a kind of dimension to the questions that are pressing in on me. But I can’t quite reconcile myself to the big question, one that surprisingly has turned out to be at the heart of the book. The question that is chasing me is, what's the difference between life and death; what does the journey from life to death look like? I'm almost sure there's work to be done to prepare myself for the journey. I suspect it's not the type of journey that is assertive, not one I can program out for myself. Yet I feel like I need to find what the practices are so I can know what the work is. And it's not like I don't have any answers to the questions. But the answers are never quite satisfying. I have some thoughts about what it might look like. But I admit they aren't a part of converting the overwhelming size of the existential situation into something that can be done. And so I think that right now the big practice is working on my final book. On one level there's a kind of disproportion between the question, “What does it mean to be alive?” and “What needs to happen in order to transform, transmute, out of being alive?” Maybe that’s just being alive differently, I don't know. Like there’s a disproportion between that question in it's kind of bald, existential form and the question of, “How do I get some work done on this chapter today?” But I think that getting some work done on the chapter is what the work looks like. It’s what the practices look like. The practices aren’t exotic. At one point in my life—and certainly again from time to time—I got to thinking that the mystical is the practice. I thought if things weren’t big and complicated and transformative and dense and mysterious, then I probably wasn't doing the thing right. When, in fact, it turns out that you just do the work. I’m at a threshold and I’m being given The Fool’s journey yet again. Where, for all of the immense amount of work that I've done on myself and with others, the last number of years on this journey with cancer, there's still, of course, a part of me that has yet to realize I'm starting again. I don't know if I am. But The Fool is stepping out into space not knowing where the feet are going to land. It feels like the right practice and yet it's a kind of ironic response to where I find myself, which is: How do I continue on this journey?” |

I’ll miss my friend, but he’s on his next journey. Perhaps our paths will cross again. Who knows what the cards hold.

Liz Grumbach

Gaymon was a man that knew all the words that needed to be said, and also consciously and consistently made bright, encouraging, open spaces for others to speak. My memories of him are so expansive that it’s hard to speak to one—the words escape me even as I remember the deep silences he intentionally held so we could think and create and build together. In every space, every moment, he transformed what was difficult into what was possible. He was a mentor, and healer, and spiritual alchemist for so many.

I have moments that flicker in my mind’s eye when I think of Gaymon. I hear the excitement and awe in his voice after we wrapped the event in D.C. that would come to inspire the future mission of the Lincoln Center; I hear the raw joy in his voice when he first spoke to me about meeting Tamara Christensen, the woman he would fall deeply in love with and marry in 2021; I can grasp at the moments planning our first design studio on Home, knowing we had something in our hands that was essential to bettering our collective futures during a time when the pandemic made futures difficult to imagine; and, going back further, I can relive moments of happenstance and running into each other, from the moment I joined ASU in 2017 to his passing: trading music recommendations, talking Game of Thrones in the hallways of Ross-Blakley Hall, encountering his skateboarding figure on campus and knowing he’d stop to say hello. But the moment that I’ll never forget: when I returned from a long time of illness and uncertainty, his kindness welcomed me back into an intellectual and creative space that let me thrive. He made it possible for me—and so many of his friends, colleagues, and students—to be part of a vision for our profession that was generous and compassionate.

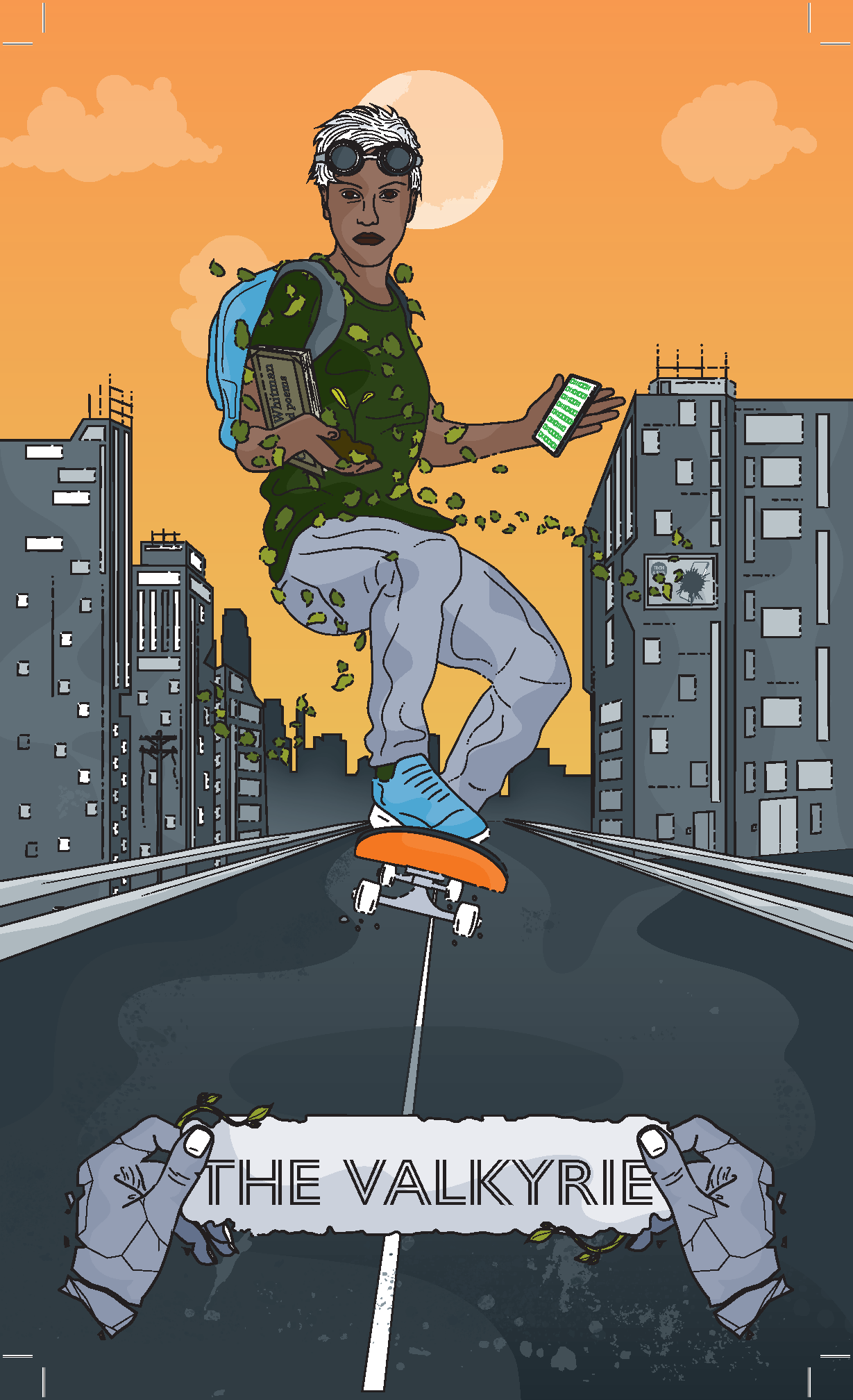

During these past few years, we talked often about the power of the moon and the sun, of cycling through space and time with meaning and attention, of attending to and moving forward with hope, even in grief and sadness. The week that Gaymon left us, I was in the classroom with students giving a lecture on finding the human(e) in technological innovation, using a tool we collaboratively created in the Lincoln Center that made physical many years of insights and conversations: the Humane Tech Oracle Card Deck. As I led my students through an exercise, I glanced up at my slides, and projected on them was the figure of The Valkyrie. And there Gaymon was on the screen, riding his skateboard into the future.

Looking at The Valkyrie, I felt a deep and overflowing well of gratitude for the lessons he taught me: the journey (modality) is just as important as the destination (product); moving forward towards emergent knowledge and innovation is powered by being with(in) the flow of life; and, if we tap into our inner strength and live our values, we will build the ethical, just, beautiful world we want to see. The figure of the Valkyrie—this card that will forever recall Gaymon’s presence for me—holds in their hands the tools for growth, for leadership, and for hope.

I will always be guided by Gaymon’s faith in hope. I will always hear his call to “attend to the possible.” I will hold firm his promise to listen deeply to others, always.

Gil Stafford

From Gil’s recent post on his Substack, Alchemy, Tarot, and Soul, where he will continue to post updates on his own Craftwork as Soulwork updates, and Gaymon’s final book, which will be published posthumously:

“A dear young friend has recently succumbed to cancer. Chaos is swirling everywhere: grief, regret, anger, confusion. My friend’s family and close associates are suffering. Emotions are on full display. Each of us is processing our feelings in different ways. There are those who need to do something: bake a cake, clean house, do laundry, go to the gym, go on a long run—or all of it, every day. Others need solitude. Depression creeps through many of us and we feel paralyzed. A few turn to their religion for solitude. All of these are appropriate responses to the chaos of loss.

Alchemists encourage us to embrace the chaos. Acknowledge its presence. Give it a name. And invite it into our circle. Making friends with grief may be the most difficult task of being human. But being present to grief may be the most conscious thing we’ve ever experienced.

I flip through my Tarot deck looking for cards that express my feelings: Death: I hate you. Three of Swords: all pierced through my heart. Ten of Swords: each stabbed in my back. Lovers: I feel so lost without my friend. Three of cups: sisters of mercy, grace, and love come to comfort me. Strength: I don’t have any, but I desperately need some. Each card joins my circle of chaos. I ask them to listen to me wail, moan, cry. My journal is a sea of words, colors, and tears. And one by one, each card speaks.

They remind me to be present. To be myself. Those are the only things I can do. But I don’t want to. I want to run away and hide. I stood up. I step out of my circle. I walk to the door. I turn back to see if they’re following me. But the archetypes of my experience remain in the circle. They begin to sing two words: love sustains. I can’t sing those words. I’m not ready. But they sing for me. A gentle breeze drifts across my face and I hear my soul sigh. And I return to the circle of The World. The Fool arrives and the pilgrimage of craftwork as soul work begins once again.”

Barry Brown

What to say about Gaymon that captures what so many of us received from him? What made him so alive to us? He was a person of many gifts which, on their own, were honed and crafted by his deep work and kept in an abiding rhythm of grace. He was so gifted, but there was something more about him than his talents. It was his spirit. The gifts were simply flashlights to something he carried inside. I have met people with great gifts but seldom have I sat in the presence of someone that offered the depth of spirit. When I was with Gaymon parts of me would resonate. He was a living tuning fork... sending a frequency of empathy and wisdom out into the world. I will miss him for a long time. He is a unique soul who put his intellect in search of wholeness as he journeyed through the Shadow to find keys of healing. I have sensed his work is not done but will be extended in ways as varied and creative as he was.

Karina Fitzgerald

I knew Gaymon for such a short time, and yet the impression of him and his life is so firmly etched into a corner of my brain, tucked in the walls of my mind like the treasured findings of a house mouse. After months of working together online, when I joined the Lincoln Center in 2022, he remarked upon our first in-person encounter by saying, “Here you are, in the flesh! You are carbon and material, and not just a face in a virtual box!” He was accompanied by his dear companion and love, Tamara, and his longboard, and a Diet Dr. Pepper (his precious Diet Coke, unfortunately, was not available).

Then, and even up to the last weeks of our time working together, I was almost intimidated by the presence he commanded; by his ease of being. His sense of fairness and kindness was unparalleled. I imagined myself a very fortunate sponge, greedily absorbing every morsel of wisdom he shared in space with others. I would sit in awe of his raw vulnerability, moved to tears by his keen insights.

A small fact about me that my close friends know well is my staunch, almost comical fear of dying. I find, even now, that the sense of indignation and injustice I feel—that Gaymon did not have more time in this life—robs me of breath. My mind lingers on those last months he shared with us, and how in circumstances that would paralyze me, Gaymon still sparked so much joy and exuberance for life. “Attend to that which is precious,” he’d say—and he certainly did. Even in death, Gaymon is teaching me so much about living.

Transmuting the Darkness into Light

by Tamara Christensen

So many have written about Gaymon the academic, the intellectual, the teacher, the collaborator, the co-designer, the friend, the human. I am grateful that I was familiar, in some way, with his many multitudes and that I also had the pleasure of knowing Gaymon the adoring husband, the proud son and the doting step/father. If you know how much the concept of soul meant to Gaymon and his work, you know that I do not use the word lightly when I say that Gaymon was, and continues to be, my soul mate.

I, like others who knew him, feel robbed that we did not have more time together on this earth because he has so very much left to give, to share and to teach us. An essential message Gaymon often shared was simply “the work you do does you.” He believed firmly that we can not escape the imprint that our labor makes on our personal and spiritual development. His framing of ethics (at least in our conversations) centered around the relationship between our choices and our lives, and how they each shaped the other.

I met Gaymon in August 2019 during an ASU Leadership Academy that he was part of, and that I attended in order to lead a short session. When I walked into the room another session was underway and wrapping up. I scanned the walls, covered with large flip chart sheets filled with responses to the prompt “What does a great leader do?” My eyes landed on a single line. It felt like a movie; everything went out of focus except for one phrase that seemed illuminated in my vision.

I had seen these words before, earlier in the year, when I attended a yoga retreat and, during a meditation meant to reveal our life purpose, this phrase bubbled up to the surface of my consciousness. I cherished this message and wore it in a bracelet to remind me of my mission. Then suddenly, in that hotel conference room, I saw those words again, written by someone else’s hand. I was startled. And curious.

As soon as the session ended, I went to the table and asked “Who wrote that?” indicating that fateful phrase.

All hands immediately pointed to a man who turned to face me and when our eyes met, I knew. I knew that those words were not just for me, but they were also for him, and for us and for whatever was to come. “Transmute the darkness into light” brought us together and continues, to this day, to remind me of what we meant to each other and what Gaymon most wanted to communicate through his work and his life: do not fear the darkness for it is where the potential for growth lies waiting. When we face our fears we are able to release the hold that they have on us and we free ourselves to make choices rooted in love and light.

Gaymon and I shared a creative intimacy that flourished through our explorations of soul, innovation, co-design, facilitation, alchemy and work with light and shadow. We designed workshops together and experimented with new “forms and norms”- as he would call them. I was astounded by his brain and capacity to weave together concepts and recall, verbatim, quotes and passages from diverse texts. Our collaborations felt fertile and mystical.

I was also astounded by the breadth and soulful wisdom of his web of friends and colleagues, especially when he found ways to bring them together. Through his work at the Lincoln Center, including development of the co-design studios with his courageous colleagues, he was able to manifest a modality of applied ethical inquiry that celebrates our human-ness while examining our reflexive relationship with technology. This work was a dream come true for him.

I hope that all who know Gaymon felt the tender care with which he held space and the spirit of generosity, enthusiasm and love that he brought to every interaction. May his work and life inspire us to face the darkness with hope and allow life’s challenges to transform us. May we do the hard work and let the work do us. As we extend his legacy into our lives, we ensure that he lives on as an essential element in the alchemical processes of our own growth.

"For anyone who has gone through the darkness of the grave in their own life, the power of redemption is that, in the midst of despair, you find the Spirit still holds you." —Gaymon L. Bennett, Jr.